The

Moons of Jupiter – Then & Now

The View from Galileo’s

Telescope

On January 7, 1610 Galileo

first viewed Jupiter through his telescope. What caught his eye was not the planet itself, but three bright

stars that were arranged in a perfect line on either side of the planet. Galileo sketched Jupiter and the three

stars, thinking at first they were simply a chance alignment. Some of his

original sketches are below.

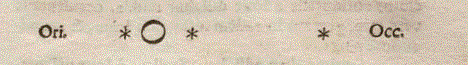

Above: Galileo’s sketches of the moons of

Jupiter made on the nights of February 3 and 4, 1610. (Ori means Orient, or East, Occ Occident, or West). Image Credit: Octavo Corp./Warnock

Library)

The next night Galileo

decided to check in on Jupiter again.

There were the three stars, but now in different positions relative to

the planet itself. The next night

was cloudy, but on the 10th, he saw a fourth star in the same

line. As he continued to study

Jupiter on successive nights, Galileo came to the realization that these four points

of light were not background stars, but mini planets orbiting around

Jupiter. The existence of four new

worlds was amazing in itself, but the discovery would help bring about a

revolution in astronomy and our understanding of the cosmos.

Was the Earth or the Sun the

center of the Universe? The debate

was raging in the first decade of the 17th century. Does the Sun move around a stationary

Earth, or does the Earth, as simply another planet, move around a stationary

Sun? Neither camp had any hard

evidence to back its case, but the Earth-centered supporters had a strong

argument. If the Earth moved,

wouldn’t it leave the Moon behind? (Remember, this is before we had an

understanding of gravity).

Galileo, a supporter of the Sun-centered universe, could now counter

that argument: If Jupiter can move

and take its moons with it, then surely the Earth can carry its Moon through

space as well. Although not proof that

the Earth moved, it was one significant piece of evidence that would help pave

the way for acceptance of a heliocentric (Sun-centered) universe.

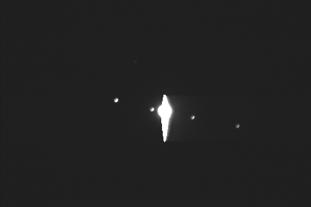

Above: MicroObservatory image of Jupiter’s

moons. Notice that the planet

itself is over-exposed to show the fainter moons.

What did YOU See with MicroObservatory?

How

do the Moons of Jupiter appear in your images taken by MicroObservatory? To see

the images in more detail, you may want to open your image in our MicroObservatory

image processing software.

In

the archive image above, the planet itself looks smeared out because it is

overexposed to show the fainter moons, Can you see the positions of the moons

change with respect to Jupiter?

The inner moons move in their orbits faster, so they will show more of a

change. If you requested more than

one image of Jupiter’s Moons, you can combine

the images into an animation to see how the moons move.

The

Moons of Jupiter - 400 years later

The moons of Jupiter are

seen today as unique worlds in their own right. The Jovian system, comprising

the four Galilean and (at last count) 23 smaller moons, has been visited by

seven space probes since1973. The

most significant mission, fittingly named Galileo, studied Jupiter and its

moons for eight years between 1995 and 2003. What do we know about the moons of

Jupiter now?

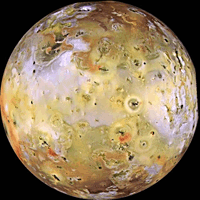

Io the innermost Galilean moon, is perhaps the most amazing

moon in the solar system. Looking like a messy pizza, its orange-yellow surface

is covered in sulfur-belching volcanoes and lava lakes. Io’s geology is so active because the

poor little moon is stretched and squeezed by the gravity of Jupiter and the

other outer Galilean moons, heating and melting its surface. (Image credit:

NASA)

Io the innermost Galilean moon, is perhaps the most amazing

moon in the solar system. Looking like a messy pizza, its orange-yellow surface

is covered in sulfur-belching volcanoes and lava lakes. Io’s geology is so active because the

poor little moon is stretched and squeezed by the gravity of Jupiter and the

other outer Galilean moons, heating and melting its surface. (Image credit:

NASA)

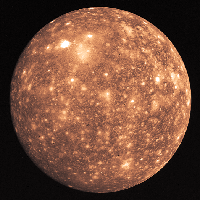

Callisto is the second largest moon of Jupiter and is about

the same size as the planet Mercury. Whereas Io has the youngest surface in the

Solar System, Callisto has the oldest. Its crust dates back 4 billion years,

just shortly after the solar system was formed. Its ancient history is evident by having the most cratered

surface of any moon in the solar system. (Image credit: NASA)

Callisto is the second largest moon of Jupiter and is about

the same size as the planet Mercury. Whereas Io has the youngest surface in the

Solar System, Callisto has the oldest. Its crust dates back 4 billion years,

just shortly after the solar system was formed. Its ancient history is evident by having the most cratered

surface of any moon in the solar system. (Image credit: NASA)

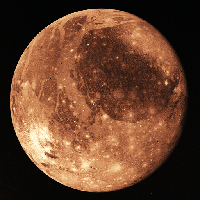

Ganymede is the largest moon of Jupiter. If it orbited the Sun instead of

Jupiter it would be classified as a planet. Like Callisto, Ganymede is most

likely composed of a rocky core with crust of rock and ice. Ganymede has had a

complex geological history. It has mountains, valleys, craters and lava flows.

Ganymede’s dark crust is mottled with bright spots where recent meteorite

impacts have exposed clean bright ice from below the surface. (Image credit:

NASA)

Ganymede is the largest moon of Jupiter. If it orbited the Sun instead of

Jupiter it would be classified as a planet. Like Callisto, Ganymede is most

likely composed of a rocky core with crust of rock and ice. Ganymede has had a

complex geological history. It has mountains, valleys, craters and lava flows.

Ganymede’s dark crust is mottled with bright spots where recent meteorite

impacts have exposed clean bright ice from below the surface. (Image credit:

NASA)

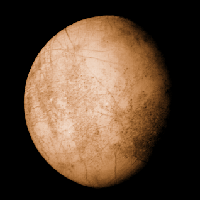

Europa is among the brightest moons of the solar system, a

consequence of sunlight reflecting off a relatively young icy crust. Its

surface is also among the smoothest, lacking the heavily cratered appearance

characteristic of Callisto and Ganymede. Lines and cracks wrap the exterior

suggest a solid layer of ice above a liquid water ocean. Liquid water is found

on only one other body in the solar system: Earth. (Image credit: NASA)

Europa is among the brightest moons of the solar system, a

consequence of sunlight reflecting off a relatively young icy crust. Its

surface is also among the smoothest, lacking the heavily cratered appearance

characteristic of Callisto and Ganymede. Lines and cracks wrap the exterior

suggest a solid layer of ice above a liquid water ocean. Liquid water is found

on only one other body in the solar system: Earth. (Image credit: NASA)

Find

Out More

2009 is International Year

of Astronomy, chosen to commemorate the 400th anniversary of

Galileo’s discoveries with the telescope.

Find out what else is happening by visiting these web sites:

The World site for International Year of

Astronomy.

The United States national site for

International Year of Astronomy.

NASA’s International Year of Astronomy

website.

Learn more about the Galileo

Mission, at:

http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/galileo/

For more information on the

planets of the Solar System, go to:

http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/index.cfm

The space probes that have

visited Jupiter are Pioneer 10 (1973), Pioneer 11 (1974), Voyager 1 and Voyager

2 (1979); Galileo (1995) and New Horizons (2007). To read about all NASA’s missions, go to http://www.nasa.gov/missions/index.html

Take

a look at the full list of objects in MicroObservatory’s Galileo activity,

and see how our understanding has evolved over the last four centuries.